By: Livia Holden[1] and Emma Varley

This piece is part of APLA’s newest Speaking Justice to Power Series, which focuses on Kashmir and marks the one-year anniversary of the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A of the constitution (August 5, 2019). The Series page is available here.

Although Prime Minister Modi’s revocation of Article 35A and Kashmir’s Special Status on August 5, 2019 has been widely interpreted as an exceptional geopolitical moment in South Asia, it was not without precedent. We argue that, in order to better understand the extent and severity of Modi’s move, we must look across the Line of Control to also consider the legislative and governmental policies enacted in Pakistan-Administered Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit Baltistan.

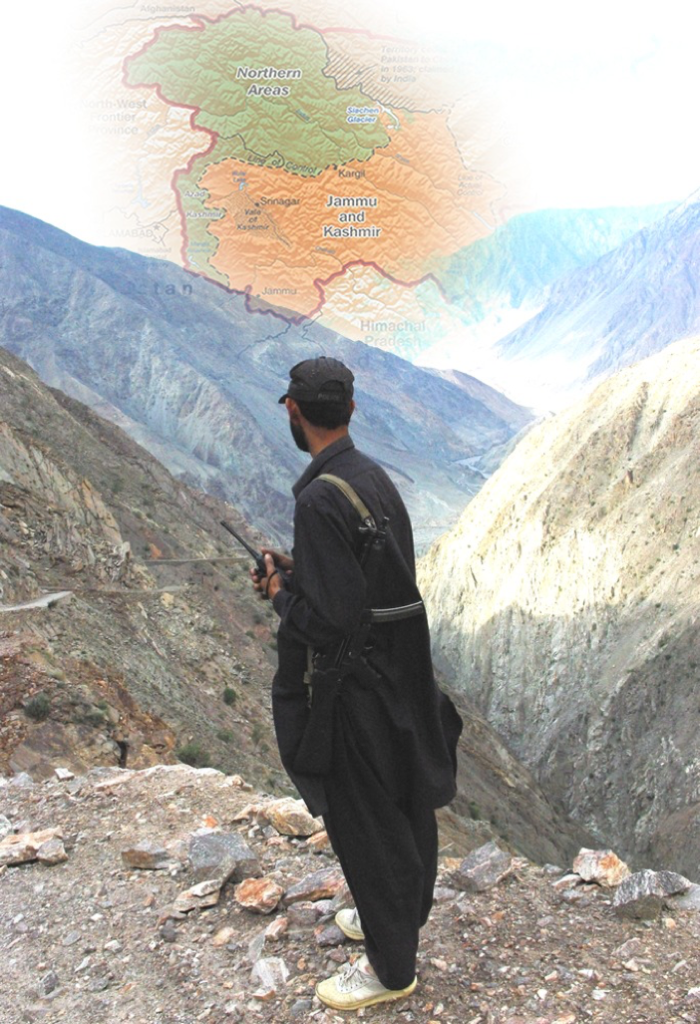

At India’s Partition in 1947, most of the territories that today comprise Jammu and Kashmir (JK; administered by India), as well as Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK; administered by Pakistan) were part of the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, governed by the Maharaja Hari Singh. Once the largest princely state in the Indian Empire, the former-Jammu and Kashmir region remains exceptional for many reasons: an area of unique natural beauty, it holds considerable geo-strategic importance not only because it borders China and Afghanistan, but also because it is the focus of the world’s longest post-war disputes.

Before Partition, the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir was populated by a Muslim majority of nearly 77%, and a politically powerful 20% Hindu minority, which, apparently, pushed the Maharaja to introduce exclusive resident-rights over the land. Maharaja Hari Singh responded by issuing a Royal Decree in 1927 that identified the people of J&K as state subjects or residents, thereby limiting non-residents’ access to major employment, establishing companies, and purchasing immovable property. There was an important exception to this rule: namely, all those living in J&K for more than 10 years were counted as permanent residents, entitling them to hold exclusive property rights over landholdings.

However, between the Residency Royal Decree in 1927 and the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the very existence of J&K as an undivided princely state was eroded. On August 14-15th 1947, when India and Pakistan as separate, independent states came into existence, the Maharaja of J&K hesitated, some argued, because he was considering the possibility that J&K could be an independent state. Before he reached a final decision, on October 22nd 1947, local troops from present-day Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir rebelled against the Maharaja who, on October 26th acceded to India. Following the insurgency, which managed to seize back territories from the Maharaja’s control, a provisional ‘azad’ (free) government was created in Gilgit-Baltistan. But on November 14th 1947 the newly founded Republic of Gilgit joined Pakistan. Not all the territory of present-day Gilgit-Baltistan joined Pakistan at the same time: Hunza was veritably annexed to Pakistan only in November 1974. Hence, the Maharaja’s accession of J&K to India was neither substantial nor fully successful.

Immediately after Independence in 1947, Pakistan and India fought the first Indo-Pakistani war over Kashmir and at the end, both India and Pakistan asked the UN Security Council to intervene in order to avoid a breach of international peace. In 1948 and 1949, two UN-resolutions advised both India and Pakistan to remove their armies from all disputed territories, so that a United Nations-supervised referendum could take place. Following the Karachi Agreement of 1949, signed by India and Pakistan under the supervision of the United Nations, the government of Pakistan divided the northern and western parts of Kashmir then under its administration into Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) and the Northern Areas (as Gilgit-Baltistan was known until 2009).

However, not only has the removal of army troops from Pakistan-Administered Gilgit-Baltistan and Jammu and Kashmir, and Indian-Administered Kashmir not happened, but people on both sides of the Line of Control have seen their special status and rights progressively challenged and reduced. For example, since the 1927 Residency Royal Decree, the notion of residence with exclusive property rights in India-Administered J&K has been progressively undermined by violent military interventions. In Gilgit-Baltistan, the Empowerment and Self-Governance Order, 2009 that granted the region limited rights of self-governance and a degree of independence from Pakistan-Administered Kashmir (AJK), was conveniently silent on residents’ exclusive right to acquire, hold and dispose of property in the region; thus, foreshadowing Modi’s revocation of Article 35A. The erosion of Gilgit-Baltistan residents’ special rights has also occurred on other fronts, including the withdrawal of food subsidies and the imposition of taxes without a corresponding representation in Pakistan’s national legislative bodies.

On May 6, 2018, it was announced that, in the interests of promoting additional opportunities for legislative, executive and judicial reform and autonomy, and to better facilitate Gilgit-Baltistan’s integration as something more akin to a province than territory, federal authorities had forwarded for the Prime Minister’s approval the Government of Gilgit-Baltistan Executive Order, 2018 which replaced the Empowerment and Self-Governance Order, 2009. Not only was Gilgit-Baltistan’s Legislative Assembly to gain additional power, but judges could finally be appointed locally, and the local administration acquired the right to establish a public service commission and take up developmental projects in tourism and hydroelectricity.

By characterizing Gilgit-Baltistan as a fifth province, the 2018 Order served to not only empower the region, but also mollify China’s concerns for the security and legality of its infrastructural and economic investments in the disputed territory. Gilgit-Baltistan serves as the primary entry point and arterial link for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a USD $60 billion project connecting Chinese and Pakistani markets, and enables China’s access to Pakistan’s southern seaports. Less often addressed were the ways the Order was intended to help stifle growing local dissent, and appease those who argued that Gilgit-Baltistan’s ambiguous status in Pakistan and its political vulnerabilities were not far different than those of India-Administered Kashmir. The years between the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self Governance Order, 2009 and the Gilgit-Baltistan Executive Order, 2018 had been marked by growing tension between the region’s pro-Pakistan and nationalist movements, with the latter seeing independence as the solution to Pakistan’s enduring failure to fully support the region’s right to self-governance and representation at the national level.

No matter its purported advantages, following the 2018 Order’s May 21st approval by Cabinet and May 27th introduction to the Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly, the response was swift and almost-universally critical. Condemnation was expressed across the region, irrespective of otherwise intractable inter-district political and sectarian differences. The size and scale of the protests, which took ad hoc and highly organized forms in Gilgit-Baltistan and major cities across Pakistan between May 27 and mid-June 2018, was unprecedented, continuing for weeks. Central to the protests was outrage concerning the quasi-colonial and, even more, ‘imperial’ powers vested in the Prime Minister by the Order. The executive authorities gained by the Prime Minister over Gilgit-Baltistan were vast and their limits largely unspecified. The Prime Minister held veto power over legislation passed and policies promulgated by elected representatives (a situation without parallel anywhere else in Pakistan), could levy taxes even in the absence of national representation, and no decree or order could be issued against him.

Among the 2018 Order’s other drawbacks, critics pointed to the fact that Gilgit-Baltistan’s newly allocated role in constitutional bodies, such as the National Finance Commission, the Council of Common Interest, and the Economic Coordination Committee, was that of a non-voting member. Civil society activists, politicians, and legal scholars also expressed their concerns that, because it was a Presidential Order rather than an Act of Parliament, the 2018 Order was ultimately unconstitutional, thus ensuring any governance benefits it afforded were unprotected by constitutional mechanisms.

Because the 2018 Order’s inclusion of Gilgit-Baltistan as a quasi-province contradicted the region’s status as a disputed territory since 1948, and challenged India’s claims of sovereignty over the entire Kashmir region, the State of India described the Order as illegal and made multiple demands for its dissolution. It was only when it became abundantly clear that regional and national-level protests would continue, and potentially grow in strength and reach, that federal authorities agreed to suspend the Order on June 21st. The stay was temporary, however. On August 8, the Supreme Court of Pakistan reinstated the Order, arguing it was necessary to fulfil the state’s promise to ensure that the people of Gilgit-Baltistan have the same respect and rights as all others, no matter its failure to see through the constitutional amendments needed to actualize and guarantee the same. Ultimately, India’s 2019 revocation of Article 35A of the Indian Constitution has a precedent west of the Line of Control. Albeit more radical and violent than the rights-reducing provisions written into the Gilgit-Baltistan Empowerment and Self Governance Order, 2009 and the Gilgit-Baltistan Executive Order, 2018, Article 35A’s repeal yielded the loss of residents’ previously protected rights to employment, education and scholarships, and land in India-Administered Kashmir. When India’s repeal and Pakistan’s reforms are considered together, their sum effect is undeniable: with the exception of Pakistan administered Kashmir (AJK), where some of these special rights still stand, the status and rights of citizens in Gilgit-Baltistan and India-Administered Kashmir have been significantly and similarly diluted, undermined, and, in important instances, eliminated altogether.

[1] This is a secondary output of EURO-EXPERT, Cultural Expertise in Europe: What is it useful for? directed by Prof. Livia Holden and funded by the European Research Council, grant agreement n. 681814.

Livia Holden, Ph.D. leads the European Research Council’s funded project Cultural Expertise in Europe: What is it useful for? (EURO-EXPERT) and a spin out project funded by Global Challenges Research Funds, UK Gender Sensitisation for Judicial Education in Pakistan and Indonesia. She is Director of Research at the Centre of History and Anthropology of Law (CHAD) Paris Nanterre and tenured full professor at the University of Padua. Among her most significant publications see: Hindu Divorce (Ashgate 2008 and Routledge 2013), Cultural Expertise and Litigation (Routledge 2011 and 2013), with Azam Chaudhary Daughters’ Inheritance, Legal Pluralism and Governance in Pakistan (Journal of Legal Pluralism 2013), Law, Culture and Governance in Hunza, (2018) Cultural Expertise and Socio-Legal Studies (Emerald 2019), Women Judges in Pakistan (International Journal of the Legal Profession 2018); Law, Governance, and Culture in Gilgit Baltistan (2019), Cultural Expertise and History, (Law and History Review Cambridge 2020) and her co-authored documentary films with Marius Holden: Lady Judges of Pakistan (Insights 2013).

Emma Varley, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Brandon University, Canada, and an Adjunct of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Saskatchewan, and Adjunct and Senior Advisor for Qualitative Research on Maternal and Newborn Health at the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Global Public Health. Among her most recent publications see: “At Odds with the Impulse: Muslim Humanitarianism and its Exclusions in Northern Pakistan.” Allegra: A Virtual Lab of Legal Anthropology, July 10, 2019; with Saiba Varma (2019). “Attending to the Dark Side of Medicine.” Anthropology News, April 17 (2019); “Monsoons and Medicine: The Biopolitics of Crisis and State Indifference in Northern Pakistan.” South Asian History and Culture (2019); “Against Protocol: The Politics and Perils of Oxytocin (Mis)Use in a Pakistani Labour Room.” Puruṣārtha (2019); with Varma, Saiba “Spectral Ties: Hospital Haunting Across the Line of Control”: Special Issue “Ghosts in the Ward: Hospital Infrastructures and their Hauntings”: Medical Anthropology (2018).